Getting through the plague: a rather rambling story of how the Worshipful Company of Glovers of London were given their 1638 Charter by Charles I, King of Great Britain and Ireland (1625-1649)

True to the times it is said that the Black Death, or at least the most significant outbreak of it, originated in China around 1334 and spread along the Silk Road arriving in Europe via Genoese galleys in 1340, and to the UK in 1348. It is thought to have killed one third of the population of the World, some 25 million people. Sometime those years appear to become defined as a single event, For others the Plague gets classified as the Great Plague in London in 1665 and 1666, perhaps because of the detailed writings of Samuel Pepys, who decided to risk staying in the City and keep a detailed diary, although he did send his wife out of town. In reality between the 1350s and 1665 there appear to have been significant plagues about every 20 years.

The plague first came to England in June 1348 through the port of Weymouth in Dorset on a ship from Gascony then a British Province in southwest France. It is thought traders were returning from Fairs in France and carried it back. They then travelled to Bristol via Yeovil, and on to London. and in three months it reached London.

More than half of the beneficed clergy in Somerset died in the six months to April 1349 and some reports say that about half the population in Yeovil also died. Artisans and craftworkers were decimated by the Black Death but we do not know how badly glovers in Yeovil were hit. What is recorded for Yeovil and district was a big shift from arable farming towards less labour intensive sheep farming because of the shortage of labour. Over the next fifty years the area became a major producer of woollen cloth. The wool industry and its exports, increasingly managed through Antwerp, was to be a major part of the growth of English economy in coming centuries. Wool sales essentially funded London’s opportunity to take over as the financial capital of Europe from Antwerp by the end of the 16th century, having been started the century as rather a backwater city.

The dates 1348 and 1349 as well as being the years when the plague hit Yeovil, are the years when we see the first written evidence of the existence of the glove industry in the town of Yeovil. In particular in 1349 an argument took place with the Bishop of Bath and Wells in the church in Yeovil over market arrangements and the record identified glovemakers as a significant, and vociferous trade in the town. According to Bob Osborne’s writing in the Yeovil History website (Yeovilhistory.info) the six named Yeovil men who “assaulted” the Bishop were two skinners, two tanners and two, Hugh and Philip, glovers. “The Bishop’s Register described the Yeovil men as ‘sons of perdition forming the community of the said town’”.

In London in the same year, 1349, not everything was stopped completely by the plague. The Worshipful Company of Glovers were given their first Ordinances. Our colleagues in The Leathersellers received their Ordinances a little later in 1398 and their Charter in 1444 and started operating from five tenements they owned near London Wall, with one of the large upstairs room converted to a well-furnished Hall, complete – as today’s Leathersellers Hall – with a notable Tapestry.

In London the various bouts of plague certainly made a big mark on life and the production of artefacts. This became very clear on a quite fascinating Glovers Livery tour of The Clockmakers Museum at the Guildhall in London. Their craftsmen worked in a tightly knit community in the city and our expert guide, a Past Master, told of two or three years over the centuries when plague swept through and killed the entire group of experts working in their City locality. In one instance an important technological breakthrough only survived because they had one member who lived and worked in Westminster rather than with the others in the City.

The Glovers started meeting in the chapel of the new plague churchyard (which according to Medieval London: the collected papers of Caroline M.Barron, edited by Carlin and Rosenthal 2017), was later to become The Charterhouse. It is apparent that at the start of the 14th century parish fraternities were quite common and met in various chapels but over the century many of these were quietly taken over by craft guilds especially where the craftworkers congregated in certain areas. It is noted that in their first ordinances the Glovers inserted very detailed clauses related to the craft of glovemaking and the wellbeing of those engaged in the trade. Matters like the procedure for sharing work should one become short were what was in mind. The move towards obtaining ordinances which carried on until the end of the 15th century is thought in some ways to relate to this trend, as one outcome of the loss of parish fraternities was a suspicion that some form of secret society was being created.

During the first plague of 1348-1351 It is interesting that despite the total lack of knowledge about the disease the government did enact some tight regulations, which have in 2020 become familiar again. Most well recorded was the isolation of those infected, and the burning of the clothes of the dead. Yet there was also extensive contact tracing and isolation. Numbers were restricted at church services and at markets, and rules laid down regarding travel and trade.

The way in which it, and subsequent outbreaks, spread around London has been fairly accurately shown by the burial records. Often it moved from the City to the East and Northern suburbs and then across the Thames to the south. This first outbreak was very much a national event but subsequent events, of which there were many, were often restricted to London or one or two other towns or centres around the country. Increasingly the problem started domestically and was not to do with imports of people or goods.

Other plague years in the 14th century were 1361, 1369, 1375, 1379-83 (this was mostly in the north but hit London in 1382) 1390-1 and 1399-1400. Between 1400 and 1530 there were about 24 outbreaks in London of which 13 were classed as widespread and involving other cities. In 1411-12 there was a nationwide epidemic, and1426 ran until 1429 also across the nation. Of the many others 1479-80 hit London very badly and across the nation and is considered the worst of the 15th century.

Given their early meeting place the glove industry was well aware of the damage being done by the plague and must have lost a good number of members, Nevertheless the industry kept going and although it was best known for complaining about imports we know of exports from Bristol in 1382 of leather gloves lined with marten skin, and others described as beaver (almost certainly meaning beaver fur lining). In 1464 the Glovers were granted their “arms” (largely as used today) in the middle of a period when, like we have seen with the Leathersellers, the big companies received their charters and other not yet established trade companies were incorporated.

For some reason fortunes dipped into reverse and by 1483 Glovers were one of many trades seeking protection from imports and an Act was passed to stop gloves being imported “from beyond the sea”. The Girdlers, Point-makers, Pinners, Pursers, Joiners, Painters, Card-makers, Wiremongers, Weavers, Horners, Bottle-makers and Coppersmiths as well as the Glovers created an interesting list of activities to be found in London at the time, all struggling – or “in decay” as the terminology of the time explains.

One aspect of these difficulties was that the Glovers gradually found having workshops in the City itself too expensive so many moved out to the East or across the river to the South and started selling their gloves through haberdashers or milliners. While this distanced them somewhat from the centres of power in the City and hugely reduced their income, handing much of it to haberdashers who were also buying imported gloves, at the same time their dispersal meant that unlike the tightknit Clockmakers they would not suffer a major collapse in numbers in any one plague.

In the 14th century leather riding gloves were popular and worn by women and men. From what Norris tells us similar styles with button cuffs and openings were worn for everyday events as well, all in leather. While the expensive pairs might have long cuffs, often slit with buttons it looks like the everyday dress glove was a gauntlet shape but without the extravagantly long cuff that we know of from the 16th and 17th centuries. The two illustrations are from Norris, page 91.

As we moved into the 15th century gloves remained somewhat plain and Norris shows an example of a pair for Henry VI. They were not exactly Court gloves as he gave them away while hiding in Bolton Hall after the Battle of Hexham. They are said, by Norris, to be of fine Spanish leather with a deerskin hair-on lining. This would certainly imply manufacture in the UK using fully tanned Spanish Entrifino (a superb Spanish sheepskin for gloves) skins and UK deer. They are supposedly in the Museum in Liverpool but I cannot find mention online so the photo below is from Pinterest where they were posted by personal.utulsa.edu and the gloves identified as the property of the Free Public Museum, Liverpool. The gauntlet goes up to the elbow and can be folded. As Norris says these were strong and useful gloves, used for riding.

Less elaborate riding type gloves were clearly a lot of what the Glovers were making in this period. We know that a lot of leather hawking gloves were produced, and that both women and men participated. The style was similar to the riding glove with a fairly long cuff and so these were often used for riding by the upper classes. Tassles were introduced on the cuff edge of some gloves replacing non-functional buttons. It seems that mittens were still in quite a lot use for working, and for the poorer people for all purposes. These would mostly be fingerless and a lot would likely have been made at home.

It was probably the case that gloves made in the UK in the late 15th century and early years of the 16th became commoditised, and the really high end were imported by those with funds and access. So I am not convinced that the Haberdashers were importing cheap foreign gloves but rather better ones, especially since much better quality sheep and kid skins were easily accessible in mainland Europe. The UK had no sensible goat population and the domestic sheep had a skin with an internal layer of fat cells which essentially makes them unsuited for gloves. Stillborn (Slink skins or morts) or very young lambskins might be used but young deer (fawns) or female deer (does) were generally preferred if imported leather could not be obtained. Hence we have an old phrase from Royal circles saying that the Spanish had the best skins, the French made the best leather and the English the best sewers. In reality all sheep from the Mediterranean areas have reduced wool and no fat layer like UK sheep so make excellent glove leather although even then it was always the younger animals that were used. Older sheep in the UK were used for hunting and hawking gloves and may well have been vegetable tanned and brown, rather than white alum tanned (tawed) glove leather.

Despite the human losses from the all too frequent plagues, the population of the City of London was in fact expanding. Initially this was no more than population growth but then it was added to by quite large numbers attracted to live and work in the city where if they were lucky higher incomes could be achieved. This included quite sizeable numbers from the home counties. London was beginning to see the creation of what we now call the suburbs. In a 1482 petition to the Court of Aldermen, only three years after settling an arbitration with the Leathersellers as to who inspected which leathers, the Glovers complained about the lax rules allowing “an influx of foreigners” to trade gloves in London. By foreigners in this case they mostly meant people from out of town, and not overseas.

A long list of regulations were approved in order to control how these “foreigners” could work “at their craft in the Citee”’ These related to quality control, rules on payment, an initiating fee, rules related to apprentices, who freemen should work with and a host of other items. Merely to read the list now makes it feel that enforcement was a forlorn hope and it was not many years before they combined with the Pursers Guild to reduce costs, and it appeared to make sense as both used alum tawed leather. Nevertheless having joined together with the Pursers in the autumn of 1498 the life as Gloverspursers was short as on 7th June 1502 they both went to the Leathersellers and agreed to amalgamate into the Leathersellers. At the time many small craft Livery Companies were falling under the control of the larger, richer merchant Livery Companies, and most of them were never to re-emerge.

The 16th century changed everything

In the 16th century matters began to evolve and the century was to be one of transformation for London and society in the UK.

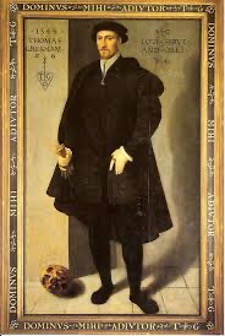

At the inaugural Glove Network Meeting at Bath Spa University in early March 2020, days before our national lockdown began, Rebecca Unsworth discussed the fact that in the 16th century it was Spanish and Italian gloves that were highly sought after, and she demonstrated this from research of correspondence at the time in which travellers to Europe were asked to obtain them. As we moved into the 17th century French gloves became more popular, German gloves get a mention and UK made gloves began to be seen. While there are plenty of pictures of monarchs wearing or holding gloves, the picture I think most emblematic is the one Thomas Gresham had painted of himself in Antwerp in 1544. As explained in great detail in John Guy’s wonderful book Gresham’s Law (2019) Gresham takes care during the sitting that every item present should send the correct message; and as we would expect he is holding a pair of luxurious Spanish leather gloves (very practical wearable gloves in fine grain leather, not fancy gauntlets with embroidery or jewels). The picture was painted in Antwerp by an unknown Flemish artist in the year of his marriage and the year he was raised to the Livery of the Mercers Company. The picture is now owned by the Mercers Company. It is also clear that when he wanted to ingratiate himself to members of the Royal Court he would offer to bring back luxury items from Europe with gloves usually top of the list. They were easy to carry, affordable luxuries and excellent at signifying wealth and status around the City. Given that Antwerp was in Spanish ownership at the time there would have been stocks to buy from, but he also had agents in Spain who could arrange getting them to Antwerp where he had a house and office.

From: https://symbolsandsecrets.london/2018/10/11/sir-thomas-gresham-and-the-royal-exchange/

Increasingly richer families were buying estates out of town to which they could quickly escape at the first hint of plague problems, and effectively isolate as community. London was again hit in 1499 -1500 and there were moments here and there in the country in 1516, 1523, 1527-30, 1532 and 1544-1546.

After this the main plague years were in 1563-64, 1592-3, 1603, 1625, 1636 and 1665-1666. In 1563, 1603, 1625 and 1665. Research by Cummings, Kelly and Ó Gráda (2016) indicate these were all roughly of equal magnitude and 20% of Londoners died within a few months each time. Research by Sir William Petty in 1682 using population and fiscal data showed that the population of London nevertheless doubled in forty years.

The way the disease spread through the community does show a clear zonal impact, so if all a trade’s craftsmen worked closely in the same street for example the outcomes could be devastating, as we heard from the clockmakers. The Glovers as we noted being more dispersed, and more numerous were not hit so badly. They were too poor to retain city workshops and stores so had moved east and also south of the river, selling their better wares via the haberdashers stores. There were certainly a lot of people making gloves and some records suggest that numbers of over a thousand make sense, quite a lot of whom would be unlicensed, and increasingly coming from European as the result of religious persecution or for other reasons. Without question they brought new ideas and skill.

In the 1563-1564 plague we get a sense of the impact on society. It was later termed the London Plague and some 18,000 died. Queen Elizabeth I was on the throne and initially ordered her household to be isolated and closed up for as long as it lasted and then six weeks beyond. Even then she felt things were getting so bad she took her inner circle out of London to Windsor and commanded that anyone arriving from London was to be hanged. Windsor was exactly where Queen Eliizabeth II sat out the 2020 Covid-19 crisis, although no one got so severely threatened: her Prime Minister used the telephone.

There was an outbreak in Stratford at the same time and coincidentally William Shakespeare was born there at the height of it, in April 1564. Stratford lost 1000 people out of a population of only 3000. His father who was a glovemaker – a white tawyer, so a wet glover (one who alum tanned their own skins) – survived, although there were many deaths in his street, and became Mayor of Stratford in 1568.

As the City of London grew the Glovers found themselves increasingly pushed out of the city to the East and over into Bermondsey and Southwark. The outcome was that soon the Leathersellers had almost no members who were Glovers, or even able to technically examine glove leather, never mind gloves themselves. In fact the big Livery companies had become commodity traders and according to Ashton the prominent leather merchants in London in the mid to late 16th century were all members of other companies than Leathersellers.

This was coinciding with more Glovers coming to the city, and the new skills coming with immigrants and religious refugees. The UK capability to make the high quality gloves and to source better raw material around Europe clearly jumped up. As a consequence the Glovers suggested that they should separate from the Leathersellers and re-establish an independent Glovers company.

Towards the end of the 16th century a curious development was occurring. There were over 1000 Glovers buying leather and they were forced, “constrained”, to buy from eight authorised sellers (Unwin, 1908), and curiously they were not Leathersellers, but mostly Haberdashers. They were well known for putting four poor skins in each dozen, which was hardly a way to endear yourselves to your clients.

The Glovers chose a bad moment for their first main push as Edward Darcy who was a courtier to the Queen bought from her a patent for £500 to inspect gloves leather with the support of the Glovers and many Leatherworkers, and then bought land in Smithfield for the inspections.

The Queen had this put through the Privy Council and it landed with the Court of Aldermen and the Lord Mayor at the start of 1592, just before a nasty bout of the plague hit. The Leathersellers had sent out a collection box to the other big Merchant Guilds, who were all very determined to keep control and not let the crafts become independent again. They, through the Court of Aldermen sent a petition back asking the Privy Council to reconsider on the 25th of February. Almost Immediately at the start of seeing the plague impacting the London Fair was postponed, the induction of the new Lord Mayor was also postponed until deemed safe. When the plague then became widespread town was cordoned off so no one entered or left and households were immediately locked down if there was any indication of the plague being present. Ships arriving in the docks were quarantined. The plague was severe in 1592 and 1593 but dragged on until 1595.

The glove matter also dragged on and is a fascinating story. Edward Darcy nearly got strung up by a mob, four senior Leathersellers were jailed for the best part of the year for “being recalcitrant” and when the Privy Council’s repeated recommendation was not adopted the Queen fined Leathersellers £4000 (about £4,000,000 today) as compensation for withdrawing the patent from Darcy although in the end it does not look like it was ever paid.

There were further bouts of the plague in 1603 and 1603 and it was in the 17th century that the UK began to see the plague doctor in his rather weird costume. It was not so visible in the UK as it was more a European thing, especially in Catholic countries.

The costume of a plague doctor featured an all-leather ensemble, a beak-like mask stuffed with burning herbs, and a top hat — which signaled that the person was, in fact, a doctor.

“The nose [is] half a foot long, shaped like a beak, filled with perfume… Under the coat, we wear boots made in Moroccan leather (goat leather)…and a short-sleeved blouse in smooth skin…The hat and gloves are also made of the same skin…with spectacles over the eyes.”

Because they believed that smelly vapours (miasma) could catch in the fibers of their clothing and transmit disease, A French Doctor Charles de l’Orme (1584-1678) designed the uniform of a waxed leather coat, leggings, boots, and gloves intended to deflect miasmas from head to toe. Probably the first hazmat suit. The suit was then coated in suet, hard white animal fat, to repel bodily fluids. The plague doctor also donned a prominent black hat to indicate that they were, in fact, a doctor. In reality most were apothecaries as the real doctors fled the city. (https://history.rcplondon.ac.uk/blog/beak-doctors) and (https://wellcomecollection.org/articles/XGaG2hAAANfAsTGg)

The mask with a long, bird-like beak was stuffed with dried flowers, herbs, and spices. The nose had only two holes, one on each side near the nostrils, and the idea was that the perfumes would filter any badness out of the air. It could also hold dried flowers (such as roses or carnations) lavender, herbs (e.g. mint), spices, camphor or a vinegar sponge. The herbs had to be very strong or very sweet and wormwood, the main ingredient in absinthe, which was very strong was preferred by some. The wooden cane was likely used to keep a distance from ill patients, rather like the current two metre rule, or to instruct caregivers on how to move them during exams.

A physician wearing a 17th-century plague preventive. Source: Wellcome Collection. Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) Taken from https://wellcomecollection.org/articles/XGaG2hAAANfAsTGg

Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence

The glove industry had only just started to use perfume in the a serious way in the UK and the Livery had been trying to build a hold on the sector, but the use of perfumes as “medicines” during the plagues, in particular in the years 1603 and 1608 meant that a three way battle took place over which livery should control the perfume trade with the Guild of Physicians and the Apothecaries was won by the Apothecaries. No doubt that the existence of the Glovers as a separate Livery being in dispute did not help.

In terms of being a protection for those in the UK who did buy perfume or use the suit the perfume did no good whatsoever of course. The suit itself, being a heavy total body cover did offer protection against the fleas carrying the plague and perhaps saved some lives. Sadly, though, the life expectancy of plague doctors was not very good.

Neither the plague nor the Glovers gave up, and after many years and failed ideas they went back to the Privy Council and King Charles I. It was clear that the big Livery Companies had control of the Court of Alderman and there was no possibility of progress via the City. In the end they found a champion in Lady Mary Killigrew, who worked for the Queen, and more than likely sourced much of her clothing including gloves. The Killigrews although both working for the Royal family were always poor and the one with a good business mind was very clearly Lady Killigrew. On behalf of the Glovers she did a similar deal with the King that Darcy had done in the 1590s and in 1638 the Privy Council put it through, in a way that the Court of Aldermen could not refuse.

Portrait of Mary Hill, Lady Killigrew by Sir Anthony van Dyck, 1638

https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/van-dyck-portrait-of-mary-hill-lady-killigrew-t07956 image released under Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND (3.0 Unported) Photo © Tate

The plague had not gone away and there had been another outbreak in 1625 while the Leathersellers were sending in more petitions against the Glovers independence and the Glovers were looking for other opportunities. King Charles understood small business and wanted to support the crafts. He liked spending money so was keener than even Elizabeth to sell the patents and provide his staff with an income from searching and inspecting goods. He could reduce his staffing costs this way.

There was another bout in 1636 and 1637 and it was this which delayed Lady Killigrew until 1638, as for nearly year there were no meetings. In the end on the 29th April 1638 the Privy Council awarded the Glovers a new Royal Charter, and that was something the Aldermen could not take away.

However they could prevaricate, and many sessions were involved to “consider” the Glovers Charter and it did not get fully enrolled in the City until 1647. It still took until March 1680 for the full ordinances, which largely control the company today, to be issued.

Plenty happened to delay the Glovers, as quite apart from the execution of the King who supported the Glovers and the ensuing war the plague came back for one more major hit in 1665-1666. This became known as the Great Plague of London 69000 or perhaps 100,000 (or 20% of the population) died in this event. It was thought ot have been mainly caused as result of more citizens travelling around the UK, Europe and the World.

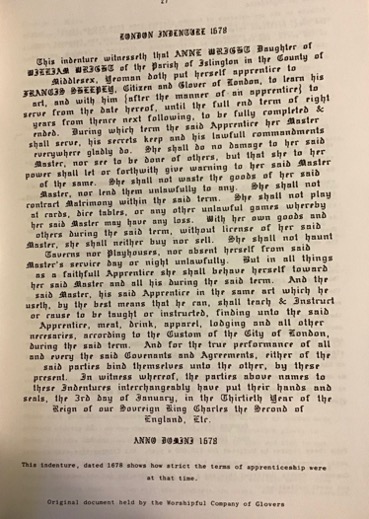

One person who would have helped celebrate the 1680 Ordinances being issued was Anne Wright of Islington. She had become an apprentice in to the Glovers in 1678, and joined quite a large group of women who were apprentices and full Liverywomen (the tern our Liveryman Jerome Farrell tells me it is appropriate. This would likely have included Katherine Clowes who had two Livery women and two Livery women in her employ in her glove workshop. Glove making was not wholly a man’s work and the Glovers always had women members from the start. The idea of cutting being for men and sewing for women is prevalent in Europe today, but certainly in the UK four and five hundred years ago it does not look like there was any such rule.

The fairly strict rules of the time for Apprentices, an eight year process, included a request that Anne Wright should not haunt the taverns. Now what Glover then or today would think of doing that?

Ashton, Robert (1979) The City and the Court 1603-1643, Anchor, UK

Guy, John, (2019) Gresham’s Law

Carlin and Rosenthal, editors (2017) Medieval London: the collected papers of Caroline M.Barron,

Cummins, Neil, Kelly, Morgan and Ó Gráda, Cormac (2016) Living standards and plague in London, 1560–1665. Economic History Review, 69 (1). pp. 3-34. ISSN 1468-0289 DOI: 10.1111/ehr.12098

Norris, Herbert (1927) Medieval Costume and Fashion, Dent, London. Republished by Dover 1999.

Unwin, George (1904) Industrial Organization in the 16th and 17th Century,

Unwin, George (1908) The Gilds and Companies of London, Frank case and Company

Waggett, Ralph (2008) The History of the Worshipful Company of Glovers of London, Phillimore