it was quite a surprise at this stage in my career to be asked to give such an important industry lecture and a great honour. I thought COVID had killed it, but made it to Wisconsin for what was an outstanding symposium

62nd John Arthur Wilson Lecture, 2023.

117th Annual Convention

Retelling “Viewing Leather Through the Eyes of Science” A Century On

Introduction

They say if you remember the sixties you weren’t there. But I do and I was. Nearly sixty years ago, still a teenager, I caught a train south from Scotland to the city of Leeds, made my way up the hill to the University and searched out the red brick Leather Industry Building in the University of Leeds. I was directed to the small departmental library with its glass fronted bookcases lining the walls and dominated by a single large table where I was interviewed about joining their undergraduate course in Leather Science.

Exactly fifty years before me, in another memorable decade, a 23-year-old Chicago born American, a graduate of New York University recently engaged as a chemist in a major Milwaukee Tannery also arrived at Leeds by train and made his way to the same red brick Leather Industry Building to be met by staff in that very same library. This was John Arthur Wilson there to learn from and work with Professor Henry Procter.

In thanking the Chair and members of the selection committee for the honour conferred upon me by inviting me to give this 62nd John Arthur Wilson Lecture I have discovered that Wilson was a most illustrious alumnus from my own University. That I worked in laboratories and sat in lecture theatres and offices unchanged from the ones he used, probably visited many of the pubs he used and travelled in and out of town on the same number one public transport route, and electric tram in his time, a bus in mine.

John Arthur Wilson

The prolific research and writing that Wilson did in these years at Leeds and after his return to Milwaukee culminated in two publications. The Chemistry of Leather Manufacture was published exactly 100 years ago this year and then in 1924 the Shoe Trades Publishing Co. produced “Viewing Leather Through the Eyes of Science”, mostly based on essays he had written for “American Shoemaking” and “The Leather Manufacturer” and it is this which forms my subject. Looking at the current landscape what would Wilson be working on if a 2nd edition were being prepared for publication in 2024.

“Viewing Leather through the eyes of Science”[i] was about communicating the business of leather to a wider audience. Wilson was convinced that knowledge should not be held by the elite but shared in normal language to others outside the industry. This meant primarily those who used leather in their products, but also to those curious about the science being uncovered around the products of everyday life.

At the start of the 20th century the UK leather industry was slipping behind both the USA and Germany in size but it was still leading in terms of research, and Leeds was the hub.

In Leeds Wilson met Joseph Turney Woods whose work in his own tannery laboratory in Nottingham had led to replacing dog dung in bating. Woods was also a member of the leather industry advisory board for the University and an external examiner. Edmund Stiasny had moved to Leeds from the Vienna Imperial Research Institute in 1909 in preparation to take over the department when Procter retired in 1913. In January Professor Stiasny launched Nerodol, with a lecture in London. It was the first ever synthetic tan based on Stiasny’s patent in a deal he had made with the producer, BASF[ii]. Procter had generously redirected his retirement gifts to fund a research laboratory where he stayed on as an Emeritus Professor[iii]. Ward, the final leather Professor at Leeds, noted this was the most prolific research period in the near hundred years of leather at Leeds University[iv].

The following year Wilson was reminded of the strategic importance of leather when the Great War erupted. Stiasny did not make it back from a trip to Austria and Procter was asked to return to head the department. The CEO of the Booth Group, George Booth, agreed to become the Director General of the Ministry of Munitions at the request of Lloyd George, who was to become Prime Minister in 1916. The UK lacked the logistic skills which the Booth Group had as a shipping line owner and from decades of experience of moving goods back and forth across the Atlantic. His father Charles Booth hurried back from a private meeting with Theodore Roosevelt on Long Island to take back day to control of the Booth leather business. Roosevelt had asked him to come to discuss trade unions.

Despite all this from Stiasny’s arrival through to the end of the War Procter was able to bring to fruition researches he had begun in the 1890s on the swelling of skin and gelatine”[v] aided by scientists such R. A. Seymour-Jones, W. R. Atkin, D. Burton and of course Wilson. Wilson was in Leeds during momentous times for both the world and the leather industry.

Shortly after the end of the war other external matters began to beset the leather industry, with major destocking in the USA. According to Watson[vi] demand for cattle hide leather then declined considerably from 1920 on resulting from:

– technological change

– the appearance of substitutes

– new modes of living

– economic weakness ending in the Great Depression

Watson says: “as far as is known, this was the most important shrinkage in demand ever experienced in the industry”. You could well be reading about today with the Financial Crisis, COVID and the invasion of Ukraine all replacing the Depression and the difficult years beforehand. Wilson understood technological change, new materials, geopolitics and societal evolution as the constants we work with.

In the opening lines of “Viewing Leather Through the Eyes of Science” Wilson says: “that leather is the most suitable material known from which to make shoes is so obvious from everyday experience that any argument brought forward would seem to be an unnecessary waste of words.” Amazingly until recently this was still a common industry tale.

On the other hand, Wilson’s said that “it is not so widely understood just why leather is the ideal shoemaking material” and this information should be made fully available. “Knowledge of the wonderful structure and delicate mechanisms of the skins are too often left to specialists”.

He wrote many articles about the underpinning values of leather; values that can easily be forgotten with over-familiarity. He understood the relevance of communicating to a wider audience and continued doing so while still busy doing in advanced research.

He was of course right that leather was obviously the best material for shoes at that time. For footwear and many other sectors leather remained essential, even strategically so, as he had been harshly made aware of during the war. Today there are no significant areas where leather cannot be replaced by alternative materials so leather’s competitive situation needs full and continued communication.

That is why I commend the latest Get the Facts campaign from Leather Naturally and hope you will all work to get that QR code spread widely throughout the world and on emails, packaging, promotional material and trade stands.

Looking at the business and technical landscape that we have today, so similar in many ways with that Wilson was dealing with, we should consider three related and overlapping leather science areas that I am convinced John Arthur Wilson would be wanting raised at this117th Annual Convention. These are research, biomaterials and chromium.

Research

Wilson often told his audiences that various areas of leather making remained unresearched and were still using historically evolved methods. He was determined to enlarge the area of properly understood science. He wanted to emphasise the fact that leather should largely be an engineered product. One which customers of every sort could rely on to meet specifications day after day.

To achieve this and to advance leather in every regard Wilson was strongly invested in research as an industry underpinning.

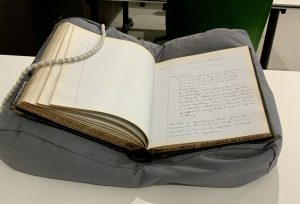

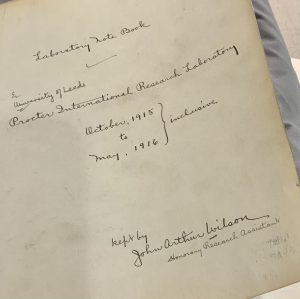

His dedication to research hit me strongly when I returned to Leeds and the University Archivist carried out a big grey cushion with a large notebook sitting on it. This was Wilson’s laboratory notebook, written entirely in his own hand, and whose 381 pages detailed his research work in 1915 and through into 1916. Leather Science might no longer be taught at Leeds, the old leather buildings might have been demolished but I still felt I was sitting in the room with John Arthur Wilson. He was there in his double-breasted suit and colourful tie explaining the effect of various acids on chrome tanned leather he had cut neatly into 8 square inch pieces.

JAW’s Research Notebook

As well as looking at chrome leather he continued the work on the effects of acids on the swelling of protein to build a picture of the main features of the changes in volume of hides and skins through the wet stages of the leather production.

His Laboratory Notebook includes notes of a lecture he read to the Nottingham section of the Society of the Chemical Industry. After describing the theoretical problems he had found removing chromium from tanned leather he quickly moved to a long list of what he termed “Possible Practical Uses”. These included extracting chromium from shavings for gluestock, stripping chromium from splits to make tanning with quebracho or mimosa easier and avoiding case hardening.

Chairing that meeting in December 1915 was Joseph Turney Wood, who had only just been told that his only son had been killed when the machine gun post he was commanding had been overrun. War was never far away.

As Ward[vii] explains Wilson and Procter jointly produced the full formulation of what became known as the Procter-Wilson theory. Wilson did most of the practical work for two papers they subsequently published in 19l6[viii][ix] setting out the theory and its experimental confirmation. Further work was done in conjunction with Loeb[x] on the swelling of gelatine in acid, and ultimately the Donnan Equilibrium was named and is now thought to offer a more complete picture. This is based on the swelling being mostly due to the unequal distribution of the ions of the acid inside and outside the gelatine.

According to Ward this work “formed a fitting intellectually satisfying and practically valuable achievement to crown Procter’s scientific career”. Having played such a central role Wilson must have returned to the Chief Chemist post at A.F. Gallun in Milwaukee proud of what had been achieved and energized by the importance of research.

Research is integrated throughout his book. Knowledge of the structure of skin is vital to anyone who makes or uses leather. The Gallun tannery had “equipped a laboratory devoted to studies of the composition and structure of animal skin”. He writes at length on scientific control describing the laboratories at A.F.Gallun and Sons as occupying the entire 5th floor of the large main building.

Other laboratories covered all materials entering the tannery, checks on hides and liquors during process, bacteriological work and the study of microorganisms, with another holding the most advanced testing and control equipment.

The final laboratory was “virtually a complete miniature tannery in itself”. “Here”, he writes “all the new ideas originating in the research laboratories are subjected to the most rigid tests before being tried on a large scale.”

Wilson’s view of research is a useful starting point for consideration:

– To eliminate problems from variations in composition of incoming materials

– To prevent deterioration in the established operations

– To advance the science of leather manufacture

We can all agree this list except that advancing the science has slipped away from the tannery as has much on the structure of skin. of the work on raw materials.

Apart from close to market developments and seasonal ranges most fundamental work transferred into national research laboratories or moved to the leather chemicals industry. The BLMRA started in 1920 and we know Turney Wood collaborated successfully with German chemical companies to obtain commercially viable bates. Stiasny really pushed the concept of collaboration when he took what he described as his “super patent” to BASF persuading them that it needed a well-resourced company to successfully exploit the many products that could be evolved from it.

As the industry changed in the second half of the 20th century the research organisations lost their local industrial base and most sources of government finance. With only a few exceptions they have switched into testing and consulting houses. Most research institutes in the newer economies are still finding their feet, Chemical companies have been reorganising and consolidating to meet new competitive challenges including the costs of servicing a much-dispersed customer base and have had to divert resources towards the high cost of compliance to meet regulations such as REACH.

Research is complex. I was reminded recently that we still wash our clothes in a drum. Fair enough, but is it not wise to question why we continue to depend on aqueous solutions with rapid uptake in the first hour, then hang around endlessly for the last few per cent to get taken up, and still end with dirty water? Should we still be using difficult materials like sulphide?

The machinery side has given us many advances in recent times. There are several far thinking companies investing considerable sums searching for not just the known unknowns but the unknown unknowns. And Kanigel explains that one of the reasons nonwovens improved in the 1990s was that collaboration with Italian tanners found that dyeing and fatliquoring in drums gives a much better touch and feel. I am not necessarily opposed to drums.

I do not intend to demean the new materials that have come to market in the last few years; and the current work ongoing to deal with some of those in current that are problematic. But I think it is a valid question as to why we have continued to use some processes for so long and have not jumped far ahead with our product and process thinking.

To do this a lot of Wilson’s time involved looking hard at collagen, its structure and how it interacts with all manner of materials. This work feels incomplete even one hundred years and 62 JAW Lectures on.

It would be incredible to see our few remaining research hubs across the globe obtaining the funding needed to increase their work; perhaps also working with some of the new generation of talented leather scientists now working as consultants. If we could get collaborative initiatives funded this could elevate leather to the next level. Eliminating some of the difficult chemicals, making better use of the collagen that enters the tannery, finding new ways to stabilise the collagen structure for leather, and imbuing leather with advanced properties that would make it a genuine competitor to other synthetic sheet materials. A material willing to challenge conventions at every step; adapting to changing times as it has all through its long history.

Biomaterials

The argument that more fundamental research is required in the leather industry to stay ahead of competitive offerings flows into the subject of biomaterials where large amounts of finance have been steadily put into research for much of this century.

We know from history that leather is accustomed to changing end-uses as new materials such as glass, paper and textiles come along, but none has made greater inroads than the plastic polymers derived from coal and oil, creating the generic term of synthetics.

The structure of the livestock industry has meant that meeting the demands of a growing population does not lead to an increase in long-term per capita availability of leather. Fewer but larger animals, greater efficiency in raising milk yields and greater consumption of white meat like poultry all mean that the growth of leather production has been very low for decades.

The simple fact that no one keeps livestock for leather has been obvious throughout the last 100 years and was the major driver for another sixties event – the 1963 announcement by Du Pont that their new material called Corfam that was going to replace leather[xi].

There had been a host of materials such as vinyl, leatherette and leathercloth offering low-cost coverings for books and boxes made to look superficially like leather, but this was the first carefully constructed poromeric material designed with the performance hoping to match leather.

Corfam failed with amazing speed. No one who bought a first pair ever bought a second. They were too uncomfortable. Corfam was expensive to produce and shiny so put into the more formal footwear category. These were the shoes of the office and the commute where foot comfort mattered.

Apart from creating a textbook marketing disaster Corfam showed how difficult it is to copy leather and how necessary it is to understand how consumers perceive complex subjects such as comfort. In his book in 1924 Wilson uses his entire final chapter to analyse consumer research comparing vegetable and chromium tanned leather, routinely returning to the laboratory for further work so that the results had meaning for future progress in leather making and offering practical suggestions to improve comfort.

Instead, the synthetics industry found other routes into the materials covering markets by offering good properties at low prices, in a route well described by Christensen in the Innovators Dilemma[xii]. This was aided by the arrival of sneakers which certainly helped the split market while giving exposure to a better generation of synthetic materials that could be combined with leather and textiles to make attractive, comfortable footwear. At that time little mention was made that sneakers were never repaired. These synthetics then relentlessly grew market share in all areas.

This century synthetics gained ground every time raw materials rose in price without retreating in the way they have previously when prices fell. Their growth in share in footwear alarmed the leather industry who objected to their positioning and claims. Several recent JAW Lectures have discussed this point in detail, in particular Gustavo Gonzalez-Quijano in the 60th Lecture[xiii].

The good qualities that made plastic essential to 20th century life have been tarnished by critical failings that impact climate change and rapid loss of biodiversity. We should remind ourselves of them:

– They are based on fossil fuels.

– Their useful life is very short and they cannot be repaired

– They shed or degrade into microparticles in ways not previously understood, in particularly in salt water.

– In landfill the plastic element will take between 500 and a million years to biodegrade

– They are very hard to satisfactorily recycle.

It is not leather that needs replacing but all these plastic materials. Since there can never be enough leather to fill the gap then biomaterials are the best bet to move into the immense space held currently by Petro-fibres of all types.

Leather has proven difficult to match and we have seen a decade of failure. Currently only Piñatex, a cellulosic non-woven derived from the discarded leaves of pineapples appears to have reached bulk and it has a very distinct aesthetic unlike leather. A mycelium production can be expected in 2024 and there will be another presentation during this convention. What is obvious is that before long the gap will be jumped and my argument would be to not designate biomaterials as enemies of leather but potential partners.

So let me be quite clear that I support the development of biomaterials and think it right that the leather industry should increase the collaboration that has already begun. If we engage with them and share expertise I am confident we have the combined skills to create the best portfolio of materials originating essentially from nature.

I do want to declare an interest as I have given some advice to companies in the sector based on my belief that we need good materials to fight the plastics and to give vegans a better plastic free offering.

Before we go further let me also address a related matter. When people sell something which they say is essentially biobased they need to be honest and transparent about it. The discovery by shoemakers confirmed by laboratory test[xiv] that many have close to 50% polyurethane demonstrates a level of deceitfulness. It is nothing to do with marketing. Similarly saying that cows are saved from slaughter by not buying is not marketing either, it is a lie. These are areas, along with that of the accurate description of leather, where we must support our national associations to improve the laws and put more effort into enforcing existing laws.

We should remember that while bioplastics are a major improvement on fossil fuel plastics they are still plastic, so the longevity in use and end of life issues still exist. This can be a problem for leather as well as biomaterials. Some heavily coated leathers are not much better than many biomaterials[xv]. Perhaps tanners should revisit linseed oil and other such materials that were used to make patent leather before the age of plastics.

I also believe that amongst the best biomaterial producers there is full commitment, along with the necessary research funding, to complete the journey to a fully-fledged material suited to work alongside leather. The sector, like tanning, has its charlatans but most are well intentioned.

I now want to return the discussion to our raw material by quoting a few lines from a recent book by the Scottish writer and poet Kathleen Jamie writing after she visited ancient cave paintings of horses, cattle and other animals in Spain:

“There was a time – until very recently in the scheme of things – when there no wild animals, because every animal was wild; and humans were few. Animals and animal presence over us and around us. Over every horizon, animals. Their skins clothing our skins, their fats in our lamps, their bladders to carry water, meat when we could get it.”

Kathleen Jamie, Sightlines

I have been a Trustee of the UK Leather Conservation Centre since 2005 and this quote came up when we did a recent residential course for international conservators and curators. Archaeologists the world over are looking in new ways at how humans and their predecessors have made use of hides and skins for most of the last two million years.

Because of global warming artefacts that have been buried without air for thousands of years are now coming to the surface. Work done by the Leather Conservation Centre and others has made it possible for these to be properly conserved and available for study.

The work highlights the successful use of hides and skins by humans in every state from raw onwards. Hides and skins which are totally raw, parchment pure or sometimes adjusted with small vegetable material, hides treated with “leathering” oils, and then brain and smoke, alum, vegetable tanning and full oil processing. Many with no or minimal treatment functioned perfectly well in the prevailing conditions.

When Rawasami gave this lecture in 2001[xvi] and searched for Wilson’s dream of a unified definition of tanning he looked at measures such as shrinkage temperature and structural stabilization amongst other more complex ideas. Later Eleanor Brown[xvii] suggested that tanning might be better viewed in terms of protein modification than as simple crosslinking, hence the term of stabilisation of the collagen structure I previously used is copied from recent correspondence with the Director at the New Zealand Leather and Shoe Research Association.

Rawasami put it simply that In the “new material world, leather needs to perform. While mankind has striven to design and make materials with similar molecular assemblies and network structures, Nature has provided the leather chemist with an architectural marvel in the form of skin. ……. Skin encompasses in its architecture a vast array of ordered structures.”

Underpinning Wilson’s work and so many JAW lectures is this collagen structure – its architecture as much as its chemistry. Tanners do not make leather through assembly or synthesis. They do it through conditioning, that is making changes to the material to make it fit for purpose. With hides and skins that is usually best achieved by doing as little as possible

Some raw material grades can push us too far towards a commodity. Might it not be better while looking for new ways to stabilise collagen as leather to use some collagen for other purposes altogether?

Back in the 1980s the late Bob Higham and I started an abortive attempt to look at whether the bottom 10 per cent of hides and skins could be taken for leather making and used in other ways. The project did not go far as those already using hides and skins for products like casings wanted to avoid scar tissue. But times have changed, technology has advanced and the economics have changed.

Currently we have unwanted hides and skins being thrown away, and a way needs to be found to get them back into the chain, but should every hide and every skin end up as leather?

The idea of collaborative working in this area of chemistry and architecture would appear to offer great opportunities to the material world for those trying to work to the best use of all hides and leather and advanced biomaterials.

New leathers and biomaterials must consider Circularity. Braungart and McDonough’s 2002 book Cradle to Cradle[xviii] puts great emphasis on post end of life treatment as the prime objective. This does not so makr sense for leather where longevity matters so much.

The main concept behind the Circular Economy comes from Walter Stahel’s Mitchell Prize winning paper in 1982[xix]. He argues that we need to keep goods longer and repair them. His Product Life Extension concept, now sometimes called the Value Retention Process, says we should make articles that last for longer and consumers will want to keep. Using resources for the longest time possible and then repairing and refurbishing them would reduce emissions and the new materials consumed. “A new relationship with our goods and materials would save resources and energy and create local jobs” Stahel has since been working with the Ellen MacArthur Foundation and has updated his thinking in several books and in a 2016 article in Nature[xx].

Stahel’s paper feels as though it was written with leather in mind. Not all items that the Leather Conservation Centre conserves suddenly appear as glaciers shrink and permafrost melts. Most are centuries old items that have been well used and kept. Many items like drinking vessels carry initials to show they have passed through generations. Wall coverings last for centuries and the UK has four original copies of the Magna Carta.

In recent years a remarkable effort has been put in to reduce the footprint of leather in terms of water, energy, chemicals and all types of waste. Wilson wanted well managed waste, even in the 1920s. He gave the Chandler Lecture for 1928 when he was the director of research for the Milwaukee Sewerage Commission as well as Chief Chemist at Gallun. His citation[xxi] said that he made major improvements to the “sewage disposal plant for his own city of half a million people which is a valuable object lesson for all our cities but has made it operable in such a way that it may soon be returning revenues to the city”.

The work and the associated investment by most tanneries in all environmental areas has been large and consistent. As an industry we can now honestly say that we go beyond merely complying with legislative demands and are searching out levels of best practice that allow us to face the world of materials with some pride. We have tanneries and organisations that have completed their own Life Cycle Analysis and as well as using them with key accounts have made them public. This has been in stark contrast to the Higg Index, now rebranded Worldly, whose opaqueness led to its own downfall, after many years of doing great harm to natural materials and especially leather.

A collaboration with biomaterials that supported all these objectives would mean that centuries of building product knowledge, process knowledge, market knowledge and our historic understanding of the Circular Economy can be usefully applied in an overlapping area. I believe such a move can offer major growth to our industry and unlock research funding and creative thinking. It can work to push plastics out and make a significant difference to the linear disposable consumer attitude in fashion, lifestyle and elsewhere. Together we need to change the consumer relationship with products.

Chromium

Amongst the press articles I keep is one from the Financial Times in 1994 entitled Green Leather in Fashion.[xxii] It is an environmental piece promoting the new concept of wet white and hoping to start the transition away from chromium.

Thirty years on chromium still predominates. It has been the subject of major research projects to bolster its defence and for much of that time I have joined that defence, but I now think it is imperative to change.

Chromium is undoubtedly an excellent tanning material when managed properly in the tannery. That cannot reverse the irretrievable damage created by the 1990s briefing against it. The target was to persuade the automobile industry to switch. It was quite effective but it simultaneously created a consumer fear over chromium in leather by linking it to popular movies and legal cases related chromium VI. This has dogged the reputation of leather since, and all the statements, academic papers and research since have failed to move the dial. Our industry does not have funding to defend chromium as well as to fight for leather.

What is more beyond the well managed tannery, and there are quite a few that are not, the baseline arguments for chromium have changed. Few if any of the analysis of the different tanning methods, or current LCAs go beyond the tannery exit and consider matters of use or end of life.

Sizeable problems with chromium tanned leather can be demonstrated in shoemaking. Footwear companies find it harder to manage shavings and trimmings that contain chromium when trying to move towards circularity. There are also problems when the consumer is finished with the shoes. Incredibly large numbers of pairs are disposed of annually. Many are merely discarded, ending up incinerated, in landfills, or shipped to developing countries in Africa with unmanaged landfill that is always burning. The footwear industry has a big task ahead to become circular given most shoes are multi component. But if the tanning industry can offer a good chrome free biodegradable leather it would make life a lot easier.

In addition, the California Proposition 65 and new regulations to reduce the maximum chrome VI permitted in consumer goods add another layer to of difficulty, exacerbated by costly penalties and contested test methods. Pyrolysis can deal with chrome leathers and pieces but there are very few plants in the world. Using chromium will continue to be fraught with difficulty. It is time to move on.

We do have a few alternatives now after commendable efforts in the past few years, although some of older ones use worrisome chemicals. Apart from some hydrothermal stability gains in the automobile sector new leathers without chromium have generally been quite uninspiring.

Most footwear producers have stayed with chromium while many leather goods manufacturers have returned to vegetable tanning. We now need to see more progress and an attitudinal change for a wholesale move away from chromium.

It took decades for the right processing parameters to be set for chromium along with the correct choice of fatliquors and retanning agents. When Wilson was worried about the performance of chromium uppers he had almost no options for retanning fatliquoring. With a multitude of products today some committed collaboration with chemical companies should be able to fast track to products with good aesthetics and performance.

In conclusion competitive materials are not the enemy of leather. We are our own enemies. When the newly appointed Secretary of the International Council of Tanners, Guy Reaks, addressed the 1978 meeting in Argentina, he spoke eloquently about the need for marketing leather. This was my first ICT meeting and the conference room was packed.

Today the ICT has started to grow again but it is still missing key country members after problems in the 1990s. We need them back if we are to drive up standards amongst the many smaller tanners that do not want to meet basic standards. Glaring examples of malpractice do immeasurable harm to the hard being done by everyone in our industry. National Associations, the ICT and other bodies are more important than ever. We need everyone to participate and make their voice heard.

Many of these organisations have transformed their image, their thinking and their approach and embarked on great moves to promote leather solely based on proven facts and science. If we can get that platform secure we need to make the new advanced products to exploit the effort.

At his Chandler lecture Wilson was commended for his “researches in physical chemistry, colloid chemistry, and the chemistry of proteins; his application with great daring and acumen of wide and exact knowledge of the most modern advances in chemistry to the complex problems of leather chemistry have resulted in valuable improvements in processes.”

He crossed the Atlantic, he corresponded globally and worked with intense application to take leather into a new more scientific era. I am proud to have got to know him these last few months.

And I want to commend to you the very best Next Generation Material: Leather

6000 words

[i] Wilson, J.A. Viewing Leather Through the Eyes of Science, Shoe Trades Publishing Co., Boston, Ma 1924

[ii] 50 years of synthetic tannins, BASF, 1963

[iii] HENRY RICHARDSON PROCTER, 1848-1927 Obituary Notices of Fellows Deceased. Royal Society https://royalsocietypublishing.org/ downloaded 24 March 2023

[iv] Ward, A. G. Henry Richardson Procter—His Life and Contributions to Science. J. Soc. Leather Technol. Chem., 1976, 59, 61

[v] Ward, A. G. Henry Richardson Procter—His Life and Contributions to Science. J. Soc. Leather Technol. Chem., 1976, 59, 61

[vi] Watson, Merrill A.(1950). Economics of Cattlehide Leather Tanning. Rumpf Pub. Chicago Page 50

[vii] Ward, A. G. Henry Richardson Procter—His Life and Contributions to Science. J. Soc. Leather Technol. Chem., 1976, 59, 61

[viii] H. R. Procter and J. A. Wilson, J. Chem. Soc, 1916, 109, 307.

[ix]H. R. Procter and J. A. Wilson. J. Amer. Leather chemists Assoc, 1916, 11, 399.

[x] Loeb, J., Proteins and the theory of colloidal behavior, McGraw-Hill. New York, 1924

[xi] Kanigel, Robert Faux Real: genuine leather and 200 years of inspired fakes Joseph Henry Press, Washington DC,

[xii] Christensen, Clayton M. The Innovator’s Dilemma: When New Technologies Cause Great Firms to Fail. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press, 1997.

[xiii] Gonzalez-Quijano G. The 60th John Arthur Wilson memorial lecture: a future for leather! J Am Leather Chem Assoc. 2019;114:244–55.

[xiv] Meyer, M.; Dietrich, S.; Schulz, H.; Mondschein, A. Comparison of the Technical Performance of Leather, Artificial Leather, and Trendy Alternatives. Coatings 2021, 11, 226. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings11020226

[xv] Carcione, F.; Defeo, G.A.; Galli, I.; Bartalini, S.; Mazzotti, D. Material Circularity: A Novel Method for Biobased Carbon Quantification of Leather, Artificial Leather, and Trendy Alternatives. Coatings2023,13,892. https:// doi.org/10.3390/coatings13050892kk

[xvi] Ramasami, T.; Approach towards a unified theory for tanning: Wilson’s dream. JALCA 96, 290-304, 2001

[xvii] Brown, E.M COLLAGEN – A NATURAL SCAFFOLD FOR BIOLOGY AND ENGINEERING. ]ALCA, VOL. 104,2009

[xviii] McDonough, William. and Michael Braungart. Cradle to Cradle: Remaking the Way We Make Things. New York, North Point Press, 2002.

[xix] Stahel, W.R., 1982, The product life factor. An Inquiry into the Nature of Sustainable Societies: The Role of the Private Sector, Houston Area Research Center, 1982

[xx] Stahel, W. The circular economy. Nature 531, 435–438 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/531435a

[xxi] Wilson, J.A. Chemistry and Leather, Chandler Lecture for 1928 INDUSTRIAL AND ENGINEERING CHEMISTRY Vol. 21, No. 2, 1929

[xxii] Larsson, T. Green leather in fashion Financial Times, September 7, 2004

Paddle Steamer where we enjoyed a cruise and supper on Lake Geneva