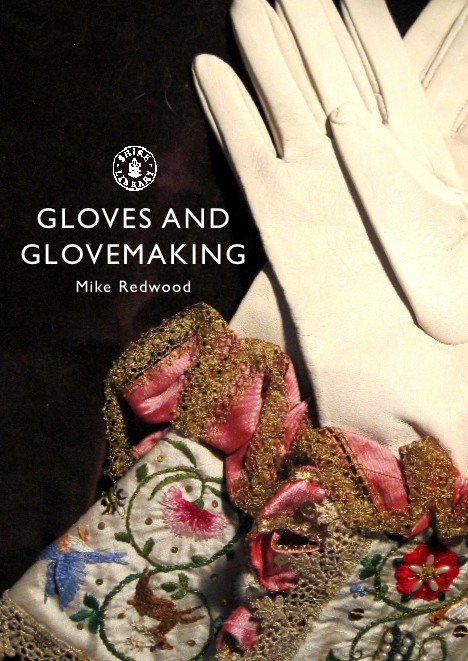

Link to buy Gloves and Glovemaking from the publishers at a discount

I have written this book on the history of gloves and glovemaking which was published in February 2016 by Shire Books and is available via Bloomsbury here as well as Amazon – the link to the latter is here where it can be also be bought overseas, and for Kindle. It does appear as of late 2021 to be often out of stock. The Bloomsbury link is correct as of November 2021 and Amazon always has the Kindle version at least. While of course I have physical copies, and anyone who has read my blog on the The Written Word (June 2021) will know, I am a lover of print and the fountain pen way of writing, the Kindle version is one I carry with me on my iPad as it is so fast to search and look things up whenever people ask questions. I have found it invaluable to have it open on an old Tablet when being questioned on the subject on line.

The book is mostly pictorial and a lot had to be left out. It is an easy read and any one interested in the subject should get one for their shelves. It is very inexpensive and the royalties I receive will go to the The Worshipful Company of Glovers of London charities. This company, the Glovers Livery, helped me a great deal in getting it over the publication line. Many colleagues from the UK industries, plus some friends in France and the USA, generously helped with knowledge and images. I owe them many thanks, but acknowledge any errors as mine. Sadly for a test of interest to quite a small sector the royalties will not come to very much.

Once you have read it if you want to fill a few more gaps and have a little more background on making glove leather you can read what I have written here. I wrote it before doing the book and do not pretend it to be fully researched. Excuse the spelling mistakes and use the contact page if you want advice or more information

Below is additional material which is mostly about leather for gloves, but also covers some other aspects of gloves themselves. It mostly covers areas not discussed in the book. Do remember this material is copyrighted and you need permission to use it.

I. Introduction

II. The Glove in History – Glove Guild

III. Aspects of Leather

IV. Aspects of Glove Making

V. Sports and Performance Gloves

VI. Glossary – see separate Glove Glossary page which is combined with the leather Glossary

VII. Date Line – see separate page

VIII. Booklist and References – see separate page

raw material

I. Introduction

“A gentleman is known by his gloves”

The story of gloves takes you through history, technology, politics, religion, and fashion. Every time you wear a pair of gloves there is a little story to be told about their origins, their significance, their construction and their purpose. And of course, you should just enjoy wearing them. Gloves are one of the affordable accessories, the small indulgences which as well as performing a useful function more often than not, have the power to make the wearer just feel better.

In this section I try and explain some of the mystery and the technology of a glove, from the materials through to the method of manufacture. Readers will find an element of repetition in the text, as the same material is discussed sometimes in different contexts. This is intended to allow each section to be read individually, and it is often useful to see the same material in different contexts.

Much of the text has been taken from the books itemised in the booklist. This booklist has been prepared as a resource for readers who want to know more about leather gloves and the leather itself. The booklist is on a separate page in technology along with a simple time line. I hope the referenced numbers have carried across correctly when we moved to this web format, which was chosen as cheaper for me to maintain.

In the glossary we have used a number of old fashioned definitions to help put gloves into their historic perspective.

II. The Glove in History

Count Alfred D’Orsay was known for wearing six pairs a day. After the reindeer gloves for his morning ride, the chamois for hunting and the beaver for the ride to London, there were the braided kid gloves for the afternoon’s shopping, the yellow dogskin for a dinner party, and then the lambskin embroidered with silk for the evening ball – this quote by D’Orsay is an abbreviated version taken from Gloves, in A Gentleman’s Wardrobe by Paul Keers

Gloves go back a long way in history. You will find them in the tomb of Tutenkhamen in 1370BC, in the Old Testament (Ruth IV.7 and Psalms CVIII.9) and much used by the ancient Greeks and Romans. In the earliest days we suppose that leaves and other material were wound round the hands to protect them from hot or cold temperatures or physical damage and they steadily developed from there.

Gloves are mentioned in the writings of Beowulf in the 8th century, and in England King Ethelred (978-1016) passed a law to make merchants from the Low Countries pay a toll that included five pairs of gloves, if they sailed in during Easter or Christmas.

So while gloves were first a protection against cold and hard knocks they soon became adopted by the rich and famous – in olden days meaning the clergy and the nobility. Indeed for a while the clergy tried to control the wearing of gloves using legislation.

It is thought that the Romans brought work gloves to Britain and the Normans brought fashion gloves. Guilds were soon set up and the Glovemakers were strong throughout Europe. In the UK the Glovemakers Guild was given its first Royal ordinance in 1347. It still exists today as in important body supporting the trade and manufacture of gloves and the education and promotion associated with gloves. In Paris glovers were organised in the 11th century and some historians say that Perth in Scotland did also. The papers that prove the latter were lost when being shipped to London but it was more likely a combined trades guild as commonly seen around Scotland. Nevertheless the making of gloves was a famous industry in this city and the organisation remains alive today, with members mostly descended from linked families.

A little more is said about The Worshipful Company of Glovers of London(of which I am a proud Liveryman) at the end of this section).

Gloves played a major role in society. They were much given as gifts amongst the rich and powerful and were always given at Coronations ceremonies.

“The record of one ceremony at Oxford in 1566 notes that Queen Elizabeth I wore a beautiful bejewelled and embroidered pair of gauntlets, and that she pulled off and put on her gloves over one hundred times so that all might enjoy her graceful hand movements”. (Ruckel)

The tradition of giving gloves at Coronations continues to this day. Another famous use for gloves was in challenges “throwing down the gauntlet”. We first read of this in 1245 via Matthew Peris, and the last challenges using gloves were in Scotland and mainland Europe in 1780s.

Even before this gloves were used both as a form of “mark” or signature, and as a sign of good faith. Gloves were passed between parties to a contract.

Gloves were authorised for use at funerals by Pope Leo I. They are still worn at many civil and military funerals. Gloves were also often used as gifts and were always worn at weddings from shortly after the Reformation.

Judges and legal personages were also frequently presented with gloves.

While there is evidence that in early times the power and prestige of gloves were kept on the hands of men early into the Middle Ages ladies became involved as well. This meant the accelerated introduction of fine embroidery and other adornments already mentioned in relation to Queen Elizabeth I. Gold and silver threads, tassels, and precious jewels were all frequently used.

The scented glove was very much part of this scene, being made popular by Catherine de Medici, from the famous Florentine merchants and bankers, in the 16th century.

These gloves were made in Italy, Spain and the UK, but France was by far the centre of excellence. The novel “Perfume”, by Patrick Suskind, is centred on this business in both Paris and Grasse. While Paris was a major centre for gloves it was in Grasse, a town just inland from Cannes on the French Riviera, where real progress was made. Already an important trading town, and famous for fine leather goods, it responded to the requirements of Catherine by producing all the aromas and putting them in the glove leather. The glovers here were also the tanners of glove leather in most instances. A few centuries later the tanners and the perfumers separated their guilds, and in the 1700s the tanneries closed and the perfumers continued as a stand-alone business. Grasse is still a major centre for perfumes and its current perfumeries are well worth visiting.

A huge variety of perfumes were used and many different methods were used to get them into the leather. Perfumes included musk, ambergris, aloe, clover, jasmine and rose. A simple way of creating and maintaining a low level of perfuming was to store the gloves in drawers or boxes containing perfume sachets. Jasmine could be made up into a type of butter and put on the flesh or inside of the leather or even the gloves themselves. While Catherine de Medici is credited with creating the fashion in Europe, Queen Elizabeth I also did so in England a little later. Elizabeth and her courtiers created a popular fashion and the smell created ridicule amongst the ordinary people, especially when the trend spread to using perfume on ordinary clothing and directly on the person. Thus began the perfume trade as we now know it. Recently, in the 21st century, gloves with aloe vera have been reintroduced to London stores and in ladies golf gloves in Japan. Lavender has also been reintroduced into leather.

Shakespeare’s father was a tanner and glove maker. If you go to Stratford and visit his house you can see where he worked and it has been recreated as it used to look. On the tanning side he was called a “white tawer” indicating that he used an alum tannage on his local skins, mostly deer. It is not surprising therefore that there are many references to gloves in Shakespeare’s writings.

These references mostly relate to less ornate and more utilitarian gloves and in the 17th and 18th centuries gloves became part of everyday wear and were used for war, work, fashion, special occasions, and for all normal business and formal wear. Many types from a huge variety of raw materials were in regular use. Specialist glove shops were common throughout Europe. Sadly to day they are only to be found in Italy, Germany and Austria. In the UK one remains in Burlington Mall in London.

In the 19th century gloves were especially fashionable, as we see from the quote at the start from the Count D’Orsay. There was actually a “club of the fringed glove” in the time of the Beau Brummel dandies.

Today leather dress gloves trend very much along classic lines, and Royalty no longer lead the changes in glove fashion. Individuals like Jackie Kennedy did have an impact in keeping the glove popular, but a return to real fashion evolving gloves looks like it is going to have to be developed from the bottom up rather than coming as in the past from the Lords and Ladies of Europe.

Since the dot.com collapse there has been some return to more formal work wear and with it the dress glove has done well. Its central role as a key accessory looks set to remain strong for many years. Elegance and feeling good still count. The recession of 2009 singles a return to sober elegance and perhaps after a cold winter in 2008/9 the dress glove trade could hope for steady business at least for a year or two.

European glove makers and tanners created this trade and still lead it today, more or less. The dress glove remains a product of character which is still designed, manufactured and consumed by and large in Europe, to the highest quality standards. The entry of East European countires into the EU has made makers in Hungary and Romania more active, and every importer has their Chinese source – some of which make excellent leather. The great move of the industry from the USA to Manila has ended and that business has gone to India and China. With costs rising in China and quality high in India the subcontinent has built a small number of excellent plants. Good dress gloves stil come from Italy, Indonesia, Hungary and Romania with Ethiopia just starting up. As costs rise arouond the world and supply chains become too long and expensive there is now evidence that some manufacturing is returning to the West where craftsmanship is coming back into fashion. Leather Dress Gloves are still made in the UK in Somerset and Wiltshire and excellent industrial gloves of various types are made on Merseyside.

An exciting and enduring product.

The Glovers Company (taken from an Installation Luncheon Menu)

London’s glove makers formed a guild sometime before 1349 when their tirst formal “ordinances-, or regulations, were made. These fixed the price ol gloves (sheepskin gloves were one penny a pair) and set standards to prevent “naughtie and deceitefullc gloves” being sold. After 1500 the Glovers’ Company was amalgamated for a time with the Leathersellers’ Company but regained its independence when a new Charter was granted by King Charles I in 1638. At this tune, beautiful hand sewn gloves were worn by every fashionable lady and gentlemen and the tiade was very profitable.

By 1800 glove manufacture was moving out of London and the Glovers’ Company declined in si/e and importance. However, in the twentieth century the Company gained new life as an active City Livery Company while retaining its strong links with the British glove trade. Today, the Glovers’ Company continues to support the welfare ol the glove trade and regularly provides donations of gloves lfor use by many charities in London and nationally. Hand-made gloves are presented to Royalty on special occasions and, annually, to the incoming Lord Mayor, Lady Mayoress and Sheriffs.

The Company makes a number of educational giants to support students with limited funds at schools and colleges associated with the City, including the City of London School for Girls, St Paul’s Cathedral School, Treloar’s School in Alton and King Edward’s School, Witley. Every year the Company sponsors a glove Design competition and Safety Poster cmpetition for students at fashion colleges and by its Golden Glove Award recognises innovation m the glove trade.

The Glovers’ Company has affiliations with units of the Royal Navy, the Territorial Army and the Royal Air f orce Cadets, all of which are actively supported.

The Company’s Cilove Collection Trust owns a collection of valuable historic gloves in the safekeeping of the Fashion Museum in Bat. This now includes a collection of Special interest gloves which were held for a time by the National Trust at Waddesdon Manor near Aylesbury. After the gloves all came together in one collection new photography was undertaken and on-line access is now available via a fabulous new website. https://theglovecollection.uk

III. Aspects of Leather

Key to a beautiful well fitting glove is a well-chosen, well-tanned leather.

Hides and skins are amongst the oldest materials used by man, and the tanning of leather one of the earliest industries. Raw hides and skins putrefy very easily so to be truly useful it is necessary to prevent that putrefaction by the process of tanning. Since the bacteria which digest hides require a degree of humidity those uses for rawhides – parchment, drum covers, panel beating hammers and the like – are those where the material can normally be kept dry, and consequently inflexible.

Leather is nature’s supreme high quality non-woven material.

Leather can be made from all types of hide and skin. The big volume supplies are cattle hide, sheep, pig and goat. All are bi-products of the meat and live stock industries. None of our leather used comes from animals bred for their skins. If we did not use them they would putrefy and waste creating an environmental hazard. Alternate synthetic materials are made from petroleum derivatives, which are finite in their availability.

Most leather is made for shoe uppers followed by garments, upholstery and leathergoods. Glove leather is a very small category which uses about 4% of the 22 billion square feet of leather made in the world.

Fine gloves are expected to fit well and leave us capable of doing many tasks, such as driving an automobile, or riding our bicycle to work. Glove leather needs to have a non-elastic form of stretch, or “run”, so that when you pull them off by the fingertips the fingers in the glove extend. When the glove is put back on the hand, pulling it from the wrist, the fingers widen again to give a perfect fit. Consequently we need skins which are naturally thin and strong. They should have a smaller proportion of grain layer compared to fibre network layer. In the past a huge variety of skins were used, as society was not rich and used all available resources to the maximum. Suitable skins are calfskins, dog skins, goat and kidskins, kangaroo, deer, horse, pigskin (especially a carpincho, which is a very fine soft skin from Argentina and Uruguay) and New Zealand dairy cattle which are thin and strong. However, by far the best skins are from the Hairsheep, or cabretta.

Cabretta The name cabretta means a little goat in Spanish and Portuguese. Hairsheep were wrongly named cabretta when the Portuguese colonized Brazil. They thought the Hairsheep were little goats and the name stuck as generic for Hairsheep, particularly after the “cabretta” skins become a regular export to Philadelphia and Gloversville in upstate New York

Above: Cabretta.

Hairsheep are found in the hot arid tropical parts of the world; such as Brazil, Indonesia, and in particular the African countries of Nigeria, Sudan and Ethiopia, plus the Middle East. Each country’s skins are a little different as climate, diet, husbandry and age at death affect a skin’s nature.

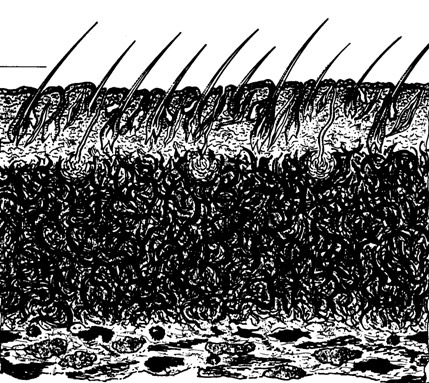

All hides and skins have a surface grain layer where the hair or wool follicles are held.

Above: Cross section of skin from hair side at the top, and flesh at the bottom.

This sits above the Fibre network layer. The fibre network layer is a three-dimensional weave of fibre bundles, which are incredibly long giving great structural strength and integrity. The bundles are made up of individual fibres, which are intertwined into the bundles like the strands in a piece of rope. These fibres are themselves made up of protein chains built up from amino acids. The grain layer, by comparison, has little strength.

The first tanning method discovered gave rise to the name tanning itself. It was based on the fact that most vegetable material contains chemicals which reacts with the fibres and tans the leather, a process probably discovered when hides or skins were first left in pools containing leaves and other rotting vegetation. The material that did the tanning became known as tannin, and the process that has been by far the most important part of tanning history over many millennia as “vegetable tanning”.

As the world evolved tanning became a localized skill and tanners looked around their environment for the best material. In the US the hemlock was most used, in the UK, oak, and elsewhere mimosa, quebracho, myrabolans were used. In some trees the fruits provided the most tannin, in others such as oak it was the bark, and in others the leaves. The tannin is extracted by soaking the vegetable in water, just like making a cup of tea: and indeed a cup of tea does itself contain a fair amount of tannin. Sir Humphry Davy was a pioneer in discovering new tannages, although some of the work done at that time with new materials and strong acids was what did so much damage to leather as a bookbinding material, as it create the problem of red heat.

While tannins from different origins vary quite a lot in colour, softness, and some other features, they all have a number of distinct characteristics. The tannin particles are large molecules which fill the structure making it quite thick, the reaction with the fibres is a loose type of bonding, and the colour is always some shade of brown now characteristic in articles like sole leather and saddlery.

Because the particle size is large the leather tends to be quite thick and stiff. Fine for some types of gauntlets and work gloves but not so good for a tight fitting glove offering either elegance or dexterity. Consequently in their efforts to make leather suitable for gloves tanners searched for other tanning methods. Two were found.

First was alum tanning, using potash alum mined mostly from quarries in volcanic areas. As well as being a good material for tanning alum was used to dye textiles and was an important chemical in the Middle Ages. So much so that in the 14th century the Vatican worked hard to obtain a monopoly on its supply and sale.

Alum gives a soft kind leather and was used extensively in gloves. Later tanners found out how to tan with fish oils – reputed to be a Hungarian 12th century discovery – and although a little smelly this also gives a soft thin leather that was used regularly in gloves. This was also a major glove leather tannage and when used on heavier skins was perfect to wear under chain male as well as for gauntlets. The US Indian brain tannage, which is also an excellent technology, is quite similar to tanning chamois leather with fish oils.

So until the end of the 19th century fine gloves were mostly tanned with alum, plus a few soft light gloves made with an oil tannage, while work and heavy-duty gloves, were made with oil or vegetable tannages.

Curiously enough the leather industry missed the industrial revolution and its moments of change did not come until nearly the end of the 19th century. But when they did come they were dramatic. A German American working with the Booth Company in the USA discovered that chromium salts could tan leather easier and faster than vegetable materials and over subsequent decades mysterious natural materials used in the “Art of Leathermaking” were replaced by more stable and appealing materials introducing rather more of an element of “Science” to this oldest of industries. The materials substituted included dog and chicken dung, flour, blood, bran, and eggs.

Chromium salts have a very small molecular size and can penetrate deep inside not just the fibre bundles but also the fibrils themselves, and then react strongly to the fibres. This allows the leather to be lighter in weight and more breathable. Heavy additions of chrome tanning materials are good for shoe leather, since they go through a double process called link-lock which create so many strong linking chemical bonds in the fibre structure that the leather can withstand very high temperatures (raw skin turns into gelatine when warmed) and so can be used for vulcanised footwear.

About 95% of the world’s leather is now tanned with chromium salts and with few exceptions this accounts for all glove leather. In glove leather we do not normally need temperature resistance and the leather is better with the minimum chrome possible.

In the 1960’s and 1970’s when tanners were looking at ways of making leather better tanners in Europe began to improve their technology and make leather much more colour fast and water-resistant. Pittards of England are perhaps the most famous in this regard. They had created a world beating water resistant glove leather and proven it in the demanding area of the Royal Air Force. This leather then became the foundation of a performance sports glove industry starting by upgrading the golf glove as well as creating a new standard for dress and fashion gloves.

So as we spend a minute or two considering the glove industry you should remember that glove leather tanning is basically chrome tanning, but with different and more technically interesting antecedents than shoe and clothing leathers. The glove tanning industry, driven by the need for soft thin material, with exciting colours, and often with interesting smells has a rich history of technology – really alchemy – much of which still remains to be properly understood and developed.

Quality and performance have two aspects in leather. We have been discussing the technological elements, but equally important is the quality of the raw material itself. Like human skins animal skins pick up surface damage through life, especially if they are living in area with a lot of thorn bushes. In particular they can get scratches and scars on their skins, or things like small pinhole damage consequent upon grass seeds catching in their hair and working into the skin itself. Tanners and glove makers make sure that serious defects do not get into quality consumer gloves, but leather is a natural material and some occasional marks go to prove its true quality and should not be viewed as defective.

IV. Aspects of Glove Making

Life was harder in older times. Man has always needed gloves for warmth and for protection. And protection was against dirt and infection as well as against obvious material things. It is not hard to imagine why gloves became so important amongst the rich and famous in society. Reference to gloves goes back many millennia.

Glove making was a major industry, which established itself in important centres throughout the world. In France, Grenoble was the glove capital, followed by Millau. In the UK Worcester, London, Perth and Yeovil were the main areas. The main glovemakers for the Court in Amsterdam moved there from Austria after the Napoleonic Wars at the request of the Crown.

Both Italy and Spain had famous glove centres and in Italy the fame of the glove makers of Naples and Florence was renowned and they remain important today. In Spain glove makers are still found in Burgos, Madrid and around Barcelona.

In Japan Shikoko Island has long been the centre of the glove industry, and in the USA Gloversville was given this name from its former “Stump City” as recognition that it was the glove capital of the USA.

Dress gloves are an exciting manufacture to the extent that a sizeable production still remains in Europe. Asia is improving fast and China, Indonesia and India produce quite a lot that are brought into Europe, but at the high end the fashion content and quality required by the consumer make it likely that dress gloves will continue to be made in Europe for some time to come. Eastern European countries have also become major suppliers of dress gloves to the world.

The manufacture of sports gloves is now very largely a Far Eastern operation, with the high labour content and low cost of plant and machinery meaning it is easy for the industry to move in the search for ever cheaper labour. This move began in the thirties when glovemakers of Gloversville moved overseas going to Puerto Rico and then on to the Far East. Production soon arrived in Manila in the Philippines, where over 50000 jobs were created, and Gloversville was never to recover. In the late nineties these jobs began to move again, going to India, Vietnam and especially to China.

In the desire for soft thin leather that would fit well glovemakers experimented with raw material as much as with leather. For most of the middle ages sheep and lamb was the prime material with kid leather from the skins of young goats being considered best for refined ladies gloves, being naturally thin and strong, with a fine soft grain or surface pattern.

Mediterranean sheep, Middle Eastern and African Sheep have also been much used, along with dog skin, pigskin, deerskin, and elk.

The big change in glove making came in 1834 when Mr. Xavier Jouvin in Grenoble discovered sizing in gloves in more detail than ever before applied. What Mr. Jouvin worked out was a cutting dye.

A second change came in 1867 when at the Paris Exposition a workable sewing machine was displayed. The introduction allowed glovemaking to move away from being a cottage industry into proper factories. Although some dress glove makers still work a cottage system, albeit using sewing machines, most golf gloves are made in modern industrial factories. The cottage system still works in Japan, Germany and the UK. It turns out to be a very modern production system to the extent that ladies (mostly women do the sewing) get delivered the pre-cut pieces of leather each week and can work a pre-agreed amount that fits in with their family life.

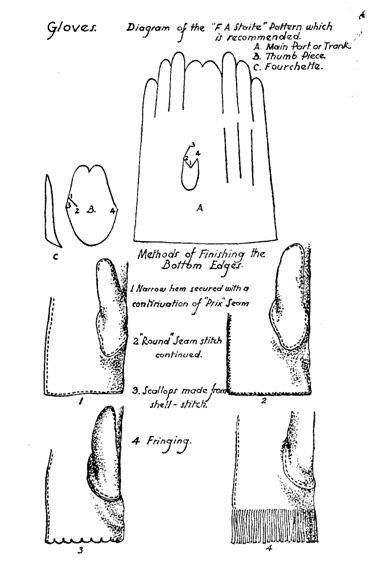

In making a glove the glovemaker cuts a large piece called a “trank” which is the palm and back of the hand, and when sewing it together adds in the thumb piece, the fourchettes, which comprise the sides of the fingers, and the quirks, which are even smaller pieces sometimes used at the finger joints. The value of a piece of leather depends on the number of tranks which can be cut from the skin.

In Europe the cutting of the leather is still carried out more labour intensively than elsewhere and should be better from a fit aspect, but quality control is made difficult by the fact that the sewing operation is mostly a cottage industry, carried out by women working at home.

Another aspect, which should not be overlooked in our understanding of the industry, is that in some countries the tanners only carried out part of what we now consider the tanning process, leaving the colouring and the finishing off to the glovemaker himself. We have already mentioned that Shakespeare’s father was one of these, who both tanned and made gloves.

A dry stage after tanning, called crust or mordant, later became the moment when sheepskins skins were traded.

There are those alive today who remember the “mordant” skins being pushed across the road on barrows from tannery to glove factory. Pittards, one of the worlds leading glove leather tanners, only learned the art of dyeing their own skins in the 1930’s, when one of the family studied the process at the famous Pavlova Leather Tannery in Abingdon, England.

The diagram below shows the main parts of a glove, being

1. The trank, which is the main part of the hand with the back and front of the fingers

2. The thumb

3. The fourchetes. Side pieces or gussets for the fingers. Six (three pairs) are needed for each hand

The patterns shown are for a glove called the F.A.Staite, which is a simple classic type glove.

Different types of leather affect the sizing of gloves. Chamois or oiled tanned leather has different stretch characteristics from chrome tanned glove leather, and for chamois the fit is normally made tighter, as the gloves will tend to stretch out in wear.

For chrome or alum glove leather it is most important that the stretch of the leather should go round the width of the hand and not up and down the length, because the strain on the glove in putting it on and taking it off affect the measurement round, and not up and down the hand.

Every piece of leather used should be tested and the pattern placed on it so that the stretch comes in the right direction. The patterns are often pieces of cardboard and when pressed down leave an indentation on the leather which is then cut with scissors.

For the glove shown 16 pieces are needed for one pair of gloves and they should all be cut at the same time to ensure the colour and appearance of all the parts are compatible.

In sewing two main stitches can be mentioned. These are the conventional Round Stitch, and the more famous Prix Seam. The latter involves putting the raw edges of the leather together and the stitching is done on the right hand side. The stitches look like normal running stitches but because of the thickness of the material the thread must be pulled through after every stitch. This involves stabbing the leather from the front and back for every stitch. The round seam is strong, can be flattened out, and has a decorative effect. The two pieces of leather are put together flesh to flesh, and the stitch goes through from the workers side to the surface. The end of the thread is then turned under round the edge and placed at the top between the two pieces, and then caught up with the stitches as you go along.

There are many fine modern threads used today although, historically silk, linen or perhaps mercerised cotton.

In assembling the pieces the “points” at the back of the glove are normally made first. These are the three rows of stitching in the form of small tucks on the back of the hand. The thumb is then inserted, after which the fingers are stitched up with the fourchettes inserted, starting with the back of the hand. The wrist is then completed and this may involve inserting a piece of elastic often using a herringbone stitch pattern.

The gloves are made inside out, and are pulled the correct way round and the ironed smooth, often being put out on an iron shaped hand which is warmed. With a little steam any wrinkles can be removed and the gloves end up with a beautiful classic sheen.

Above: Patterns for a F.A.Staite “good cut”, taken from Leathercraft Vol II

V. Sports and Performance Gloves

Gloves historically have been for protection – from dirt, disease, heat and cold. They have also been used to show distinction and wealth, but that was essentially built out of the fact that the wealthy wanted protection from these four points.

Not many areas need gloves for maximum dexterity. In sports golf is exceptional in this. The gloves are required to give constant and perfect fit on the grip of the club and must act as a second skin. They are worn outdoor and must be comfortable, which precludes the simple solution of latex or surgical rubber gloves. So golf gloves have to be made of a very thin material and fit very well. After this racquetball and baseball batters gloves come next in terms of the need for dexterity.

Racquetball is often played with a rough nodular “Amy” grip and the glove must be strong enough to withstand this, along with huge amounts of sweat. But this is a short hard game – comfort does not come into it. Baseball batters gloves are put on and off only for batting: again grip counts but not much else. Attempts have been made to introduce gloves into tennis and squash. In the US squash gloves became quite popular, but never took on in Europe. A few gloves are sold for tennis, but they have never become part of the equipment.

The big fielders and catcher’s gloves of baseball made out of 2mm special tan cowhide are a tradition of their own. Americans sleep with them under the mattress for six months before using them and hang on to a loved glove for life. They are a fine example of the potential to build on the consumers’ emotional involvement with both gloves and leather.

US Football gloves are a more recent concept, although gloves have been worn for keeping warm in snow. If you look into the history you will find that a player had some form of rosin all over his hands and body and caught the winning touch down. They then began to use gloves for the catchers that were tacky – and a New Jersey company called Nuemman made a tacky leather glove. In the early 1990s the sport thought this had gone too far and had a self-regulating grip test introduced. It also banned grippy gloves from certain levels of play.

Cycling gloves are for anti-vibration and help you when you fall as your hands go down first normally. They get hugely sweaty and often the cyclist can only pull them off inside out. The simplest style is a short finger glove which was historically made in brown pigskin, and called the “peanut” glove because of the way it looked. Some real material innovation has taken place in this area, even although prices available create limits. Kevlar, gels etc. are all very important as speeds have risen and mountain bikes have grown in importance. Some experiments have been done with a gripper glove in 3M material to link it to the handlebar grip that is made in the same material. Very effective in wet or dry and sure to be introduced elsewhere. This technology is also used in golf.

Skiing also has had a lot innovation with concepts such as heated gloves etc. Dexterity only comes in on cross-country skiing gloves, while protection is most important n snow boarding.

In soccer goalkeepers’ gloves are very important. Materials seem to be all about stopping the ball, and do not do much for dexterity. Outfield players are increasingly seen wearing knit gloves in cold weather, perhaps because so many Latin Americans and Africans now play in the northern leagues.

In rugby also we have started to see the backs wearing gloves to help with handling. At the moment we see it mostly designed to stop hands becoming numb from cold, but technologies tried in US Football demonstrate what we might see in the future.

Horse riding gloves have a controlled tackiness for holding and sliding the reins. For polo many US players think the best glove is a baseball batters glove.

Those interested in marketing will note that a glove is a great branding opportunity. If in doubt pick up any baseball or golf magazine. From the front cover on you will see the glove can be a powerful marketing tool. Hence the move in the 1990’s for nearly all the big sports brands to enter the sports glove market.

Motor sport is one of the areas where we see sports and performance gloves start to overlap. These are highly technical gloves which have to marry dexterity with abrasion and fire resistance. Historically this has always required quite high levels of compromise, but increasingly new technology is allowing leather to meet most requirements, along with other specialist materials such as Nomex.

Military and industrial uses cannot be ignored here and readers should consider the great asset that thin strong leather is in many military situations. If a tank goes on fire the glove must be fireproof, but more importantly those in the tank have only a few seconds to escape before explosion. So again dexterity counts even more and the gloves need only be adequately fireproof in order to get out.

Similarly in flight. When a pilot lands in the sea cold is normally the greatest issue, and the task is to get the life raft open before the hands get wet and too cold to function properly. So waterproof gloves thin enough to work with the raft are required. It was never thought that gloves would become so important for the ordinary soldier as has been discovered in Iraq and Afghanistan. Infra red absorbing camouflage gloves are of major importance as metal surfaces – guns, vehicles, ammunition boxes – get incredibly hot in desert conditions.

In recent years there has been a general return of the glove as part of the uniform, be it for airline staff, museum guides, or security staff. Employees who interface with the public and are expected to be smart in all weather conditions are now often being issued with quality leather gloves, which protect them against the cold and rain.

We should not ignore driving gloves, often short fingered gloves with a keyhole back. According to Paul Keers they have never been accepted as formal or business wear, and “should be left in the car – or ideally on one’s driver”. With the new move to retro design cars such as the BMW Mini and to open sports and touring cars the driving glove is making a come back and is an essential accessory for many of these new models.